We will follow up Monday's lecture on the early months of the war by getting into the main battles of early 1862. With any luck, we'll get to Fredericksburg in December, 1862.

One of the first things we need to consider before going forward, however, is a bit of military technology that changed the way we fight wars, but not before a lot of men died in the Civil War in the process of making that discovery.

This video does a very good job of showing some key elements of the difference:

But what did this difference mean to the battlefield? In short, it meant a lot! And it isn't even all entirely evident in this video. We will discuss this in class today.

The difference was even more dramatic when rifling came to artillery.

Yet technology isn't everything - and it probably wasn't even a factor in the outcome in the war per se. But it did matter more broadly in the way societies planned for and executed their war plans, and it is worth noting that the North had a vast advantage in innovation and bringing new ideas into material existence.

This blog will serve as the online companion to History 338 - Civil War and Reconstruction - taught by Dr. Justin Nystrom at Loyola University of New Orleans, Fall Semester 2012

Wednesday, September 26, 2012

Monday, September 24, 2012

The first 18 months of war

Old-fashioned military history has made a small comeback in the profession in recent years. No doubt this is in some measure due to our current military entanglements. But it is not nearly as prominent as it once was, particularly in the context of a collegiate-level Civil War class. Today, we ask a much wider range of interpretive questions about the Civil War Era than we did 50 years ago, when interest picked up during the war centennial in the 1960s. The design of this course reflects many, yet certainly not all, of this interpretive myriad. All the same, military history - the who, where, what, when - and more importantly - "why" of the battles remains important to any true understanding of the conflict. What happened on the battlefield had a symbiotic relationship with the broader changes taking place in America, having a direct impact upon their course.

Today (and likely into Wednesday and possibly next week) we will look at the first 18 months of the war. It is important to pay attention to chronology more than specific dates of battles. Yet dates also remain important. The sequence of events is key in war, because precise moments dictate subsequent outcomes. Therefore, I hope that you pay particular attention to the sequence of events and their significance during the lecture.

Explanations of battles will not get into the deeply detailed terrain of inside-baseball military history. But I will explain to you in broad strokes the key moments so you have a better understanding of how the observers and participants judged the results of the conflict.

To lend some structure to what for some will be an endless array of place and proper names and dates, I supply an overview of what we will cover:

- The clashes of 1861: May to December: Virginia, Western Kentucky, and Missouri

- The West in early '62: January to June: From Donelson to the fall of New Orleans and Memphis by way of Shiloh and the fall of Beauregard and the rise of Grant and Halleck

- The East in early '62: April through July: The Peninsular Campaign and the Seven Days' Battles / The Valley Campaign. The rise of Lee and Jackson, the first fall of McClellan

- The East in mid '62: August - Second Bull Run and the fall of Pope and recall of McClellan

- The Confederate Offensive of '62: Late August through early October: Bragg and Kirby Smith in Kentucky, Lee in Maryland.

- The West in late '62: June through December: Continued Confederate Failures: Baton Rouge, Iuka, Corinth. The fall of Van Dorn and Price and the rise of Sherman.

- The Mess in the East, late '62: October through December: the last fall of McClellan, Rise and fall of Hooker and Fredericksburg.

Note the useful LINK to the MAP on the right hand margin of this blog!

The sunken road at Antietam as it appeared in 2007.

Antietam Creek.

Wednesday, September 19, 2012

The South on a War Footing

I will want to spend a fair amount of time today discussing chapters 2 and 3 from the Escott book, but we will also spend some time considering the transformation of the South set into motion by the war.

One thing that I want us to consider today in our discussion is the role of contingency - in history in general, and in determining the root causes and objectives of the Civil War in particular. To wit, that while one thing may be absolutely true in January, it might not be in April. The mutability of the Civil War's main themes are one of the key sources of subsequent disagreement. Mutability is hard to chart. Everybody can be right if they are selective enough in their analysis. But we must chart mutability if we are to understand the war.

As I mentioned earlier, it was not as though the South was without industry before the Civil War, although the scale of it dramatically increased. The Roswell Mill in Roswell, Georgia is a good example of a factory that became much more important with the onset of war. (It was also a forerunner of the New South textile mill.)

One thing that I want us to consider today in our discussion is the role of contingency - in history in general, and in determining the root causes and objectives of the Civil War in particular. To wit, that while one thing may be absolutely true in January, it might not be in April. The mutability of the Civil War's main themes are one of the key sources of subsequent disagreement. Mutability is hard to chart. Everybody can be right if they are selective enough in their analysis. But we must chart mutability if we are to understand the war.

The roots of New South industrialization can be found in the policies of Jefferson Davis:

As I mentioned earlier, it was not as though the South was without industry before the Civil War, although the scale of it dramatically increased. The Roswell Mill in Roswell, Georgia is a good example of a factory that became much more important with the onset of war. (It was also a forerunner of the New South textile mill.)

The Roswell Mill located at rolling falls on the Chattahoochee River.

Likewise, the modest Tannehill Iron Works (just south of Birmingham, Alabama) of antebellum times underwent a massive transformation during the war. Birmingham, which did not exist at the time of the Civil War, would be founded on the iron industry that blossomed for the sake of the Confederate effort.

Similarly, North Georgia also had a nascent iron industry in Bartow and Cherokee Counties. The Cooper Furnace is representative of this period of time. The area did not develop into a major iron and steel producer, however, because the local ore deposits were not nearly as rich of those found in Alabama.

More sophisticated manufacturing took place in cities like New Orleans, where the Leeds Foundry (today owned by the Preservation Resource Center) fabricated everything from cannon to ironclad ships. The city's early loss to the Union Navy was a blunder of epic proportions from many standpoints, not the least of which was the supply of war materials.

Like other Southern industrial enterprises begun in the 1830s, the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia grew tremendously during the war. But few other factories were nearly as important.

Southern manufacturers had to be resourceful. Often times the weapons they produced contained material substitutions when possible - i.e., iron instead of steel, brass instead of iron. A good example of this can be found when comparing the Spiller and Burr revolver to the Starr Revolver picture below:

The Confederacy's need to manufacture the goods of war led it to engage in ambitious plans, including that of the national armory in Macon, Georgia. Considering the "non-industrial nature" of the South, it's construction, which began in 1863, was remarkable. It never fully realized its potential by the time of the war's end.

A photograph of the recently captured Macon Arsenal taken in June, 1865.

Yet in the end, southern manufacturing was a shabby replica of efforts in the North, where a major industrial complex began to flourish during the war.

Monday, September 17, 2012

Community and Battle of Antietam

Here is a blog entry written for Not Even Past by my former Virginia Tech student Nick Roland. He is currently pursuing a PhD in history at the University of Texas. Much like I ask you to do in your "Community at War" assignment, he links the fate of Texans with affairs on the battlefield at Antietam.

Sunday, September 16, 2012

The Civil War at 150... All around us!

Last weekend, Civil War reenactors descended upon Maryland to play out the one-hundred fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Antietam. We'll be looking at this battle a little later in the semester. If you were unaware of the reenacting subculture, however, this would be a good time to begin paying attention.

Also, PBS will premiere on Tuesday, September 18 what promises to be a somewhat morbid documentary titled "Death and the Civil War." It is, however, being produced by the people who bring us the American Experience films, so it might well be worth our while to watch it. Perhaps we might even take a little time to discuss it in class on Wednesday.

Also, PBS will premiere on Tuesday, September 18 what promises to be a somewhat morbid documentary titled "Death and the Civil War." It is, however, being produced by the people who bring us the American Experience films, so it might well be worth our while to watch it. Perhaps we might even take a little time to discuss it in class on Wednesday.

Creating an Army from Scratch

The following pictures should give you an idea of the war's ability to "make" and "unmake" people as well as institutions. The war represented a tremendous problem, but with this trouble came incredible opportunity. Many of the fundamental questions in American history for the rest of the 19th Century were in some way settled by the way fate intervened in lives of the Civil War generation in 1861-62.

Leading an army: A portrait of youth.

George Brinton McClellan - made General in Chief of the United States Army. Prior military training: extensive.

Age in 1861: 35

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. - (future legendary Associate Justice of the Supreme Court) as a young lieutenant in the Union Army. Prior military training: none.

Age in 1861: 20 (just barely)

Ulysses S. Grant - Future commander of the Union Army and President. Prior military training: substantial.

Age in 1861: 39

John B. Gordon - Major General in the Confederate Army. Enlisted as Captain, promoted by 1862. Prior military training: none

Age in 1861: 29

Not everybody was young, including political generals (the early) bane of both armies:

Leonidas Polk, the "Fighting Bishop." Kin of James K. Polk, Friend of Jeff Davis, appointed to high command despite no military experience - Was a graduate of USMA 1827. Killed outside Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia in 1864 at age 58

It is not hard to believe that Nathaniel P. Banks might one day have been President had he been at least a competent and effective general, but he was not. This former Speaker of the House became a political general at age 45, at the beginning of the war:

Both North and South had to construct armies essentially from scratch.

What were some of the considerations that the leadership had to take into consideration?

There were certainly tangible issues such as how one might pay for the war. Then there is the question of just how long the war was going to be and to what degree you were ready to disrupt your society. How many men, for instance, should stay home to keep a nation's economy operating.

We read about how McClellan ordered Hardee's Tactics printed for his inexperienced officers, but there were a lot of factors to consider that weren't going to be solved with readily available (if out of date) books.

Not only did few men have military experience of any kind, though frontiersmen North and South and slave patrol personnel in the South had some useful skills in human combat. But what of supplying an army that was larger than anything anyone had ever seen before? Who knew how to feed 15,000 ... 20,000... 100,000 men in the field, keep them moving, etc.? This required a great deal of managerial skill, and this tended to favor the captains of business in the North - if only they occupied those positions.

Some approximate figures:

Size of the Armies: Union

Jan. 1, 1861 - present for duty: 14,663

Jan. 1, 1862 - present for duty: 527,204

Confederate Forces:

Jan. 1, 1862 - present for duty: approx. 260,000

Moreover, think about something like medicine. How many doctors will a nation need? The answer was going to become clear: far more than either nation possessed. And these doctors had limited notion of the causes of infection. No wonder so many soldiers died of causes such as "camp fever."

How many engineers and manufacturers would need to be dedicated to the war effort? And again, you see that the North has a comparably large advantage. Consider again the "mechanic's' republic" as demonstrated by the daguerreotypes in the first lecture.

In Escott, you will read about Jefferson Davis's plans to supply his nation's war effort, and how radical they were, particularly in light of the South's supposed "states' rights" ideology. In light of the North's war making ability, was there any other viable choice?

Yet all of this discussion of the tangible does not tell the whole story. The United States, the world's most technologically advanced nation in the 1960s, ultimately foundered and withdrew from its involvement in Vietnam.

How important (and how strong) was the Northern commitment to Union? Did this exist in separation from the issue of slavery? Was the North truly united and could it stay united. Moreover, what did the North have to accomplish in order to declare true victory?

Leading an army: A portrait of youth.

George Brinton McClellan - made General in Chief of the United States Army. Prior military training: extensive.

Age in 1861: 35

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. - (future legendary Associate Justice of the Supreme Court) as a young lieutenant in the Union Army. Prior military training: none.

Age in 1861: 20 (just barely)

Ulysses S. Grant - Future commander of the Union Army and President. Prior military training: substantial.

Age in 1861: 39

John B. Gordon - Major General in the Confederate Army. Enlisted as Captain, promoted by 1862. Prior military training: none

Age in 1861: 29

Not everybody was young, including political generals (the early) bane of both armies:

Leonidas Polk, the "Fighting Bishop." Kin of James K. Polk, Friend of Jeff Davis, appointed to high command despite no military experience - Was a graduate of USMA 1827. Killed outside Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia in 1864 at age 58

It is not hard to believe that Nathaniel P. Banks might one day have been President had he been at least a competent and effective general, but he was not. This former Speaker of the House became a political general at age 45, at the beginning of the war:

Both North and South had to construct armies essentially from scratch.

What were some of the considerations that the leadership had to take into consideration?

There were certainly tangible issues such as how one might pay for the war. Then there is the question of just how long the war was going to be and to what degree you were ready to disrupt your society. How many men, for instance, should stay home to keep a nation's economy operating.

We read about how McClellan ordered Hardee's Tactics printed for his inexperienced officers, but there were a lot of factors to consider that weren't going to be solved with readily available (if out of date) books.

Not only did few men have military experience of any kind, though frontiersmen North and South and slave patrol personnel in the South had some useful skills in human combat. But what of supplying an army that was larger than anything anyone had ever seen before? Who knew how to feed 15,000 ... 20,000... 100,000 men in the field, keep them moving, etc.? This required a great deal of managerial skill, and this tended to favor the captains of business in the North - if only they occupied those positions.

Some approximate figures:

Size of the Armies: Union

Jan. 1, 1861 - present for duty: 14,663

Jan. 1, 1862 - present for duty: 527,204

Confederate Forces:

Jan. 1, 1862 - present for duty: approx. 260,000

Moreover, think about something like medicine. How many doctors will a nation need? The answer was going to become clear: far more than either nation possessed. And these doctors had limited notion of the causes of infection. No wonder so many soldiers died of causes such as "camp fever."

How many engineers and manufacturers would need to be dedicated to the war effort? And again, you see that the North has a comparably large advantage. Consider again the "mechanic's' republic" as demonstrated by the daguerreotypes in the first lecture.

In Escott, you will read about Jefferson Davis's plans to supply his nation's war effort, and how radical they were, particularly in light of the South's supposed "states' rights" ideology. In light of the North's war making ability, was there any other viable choice?

Yet all of this discussion of the tangible does not tell the whole story. The United States, the world's most technologically advanced nation in the 1960s, ultimately foundered and withdrew from its involvement in Vietnam.

How important (and how strong) was the Northern commitment to Union? Did this exist in separation from the issue of slavery? Was the North truly united and could it stay united. Moreover, what did the North have to accomplish in order to declare true victory?

Wednesday, September 12, 2012

Tumbling Toward War

| ||

| A young Nathaniel P. Banks |

|

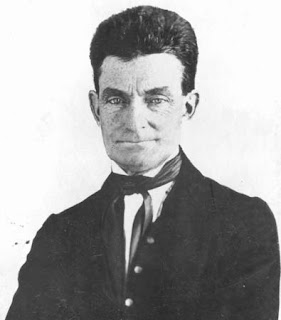

| John Brown |

Virginia and Maryland as a case study:

Slavery and Secession.

Virginia Maryland

Population 1,596,318 687,049

Slave Population 490,865 (31%) 87,189 (12%)

Slaveholders 52,128 (4.7%) 13,783 (2.3%)**

** note that these figures are deceptively small because only heads of households were slaveholders.

There is a fundamental question about the beginning of the war, and that is at what point does war become inevitable. We'll spend some time looking at the secession crisis and the efforts of some to avert bloodshed.

Why would Lincoln wish to scuttle the Crittenden Compromise? What were some of the factors in his decision? Was it a good one. Oh, and by the way, John J. Crittenden was a really interesting guy and a true patriot.

The bombardment of Fort Sumter precipitated a sort of hysteria that accelerated the march toward war, whether it was the subsequent secession of Virginia or the rage militaire described by James McPherson that took root in communities, North and South, all over the divided nation.

Here is an interesting page with links to images of Fort Sumter AND a live webcam of Fort Sumter. There is another web page promising a "pan and zoom webcam" of Charleston harbor, which would be really awesome if it actually worked!

On the eve of war, the North clearly possessed important material and demographic advantages over the South, but one must remember that the definition of very different for the two opposing sides. It is important to keep these competing definitions in mind when considering big-picture strategies and outcomes.

The war that most Americans envisioned in May, 1861 was based on notions that had become obsolete. Even among those who appreciated the potential for the coming war's devastation would probably have had a hard time imagining just how fundamental the war would reorder American institutions like the way we as a nation fight a war. By the Christmas of 1861, Americans were only beginning to understand the magnitude of what was afoot.

Monday, September 10, 2012

The Valley of the Shadow

We will spend a little time today looking at the Virginia Center for Digital History's "Valley of the Shadow" project. There are several reasons why:

1) The project opens a window onto the way that slavery shaped life within a community, and as a result, the topic is apropos to what we will cover today.

2) Valley of the Shadow reflects the sort of community study that we will be doing, albeit in a much smaller way, with our "A Community at War" research project

3) It opens a larger discussion of "doing digital history." At one point, the VCDH was one of the leading institutions in the field. A current perusal of their site seems to suggest a significant amount of stagnation. At the same time, other institutions like George Mason University's Center for History and New Media seem to be taking the lead. Why is this?

In addition to a discussion of Nelson & Sheriff chapter 1 and some lecture material on antebellum slavery in general, we'll spend a little time going over the "Community at War" assignment.

1) The project opens a window onto the way that slavery shaped life within a community, and as a result, the topic is apropos to what we will cover today.

2) Valley of the Shadow reflects the sort of community study that we will be doing, albeit in a much smaller way, with our "A Community at War" research project

3) It opens a larger discussion of "doing digital history." At one point, the VCDH was one of the leading institutions in the field. A current perusal of their site seems to suggest a significant amount of stagnation. At the same time, other institutions like George Mason University's Center for History and New Media seem to be taking the lead. Why is this?

In addition to a discussion of Nelson & Sheriff chapter 1 and some lecture material on antebellum slavery in general, we'll spend a little time going over the "Community at War" assignment.

Wednesday, September 5, 2012

TIME Magazine editorial piece

I'm not asking you to accept this piece uncritically, but I thought some of the concepts of historical memory that it evokes are worthy of discussion. Please view it when you get a chance.

Tuesday, September 4, 2012

Sunday, September 2, 2012

Antebellum America

Maybe your perception is that life was slower in antebellum America, but nothing could be further from the truth. Everything was quite literally in flux.

Between 1840 and 1860, the United States underwent many transformations. The following are a few of the important ones:

Students of the Civil War rightly focus a great deal of attention on the antebellum period in order to ascertain the moment when "it all went wrong." Historians, of course, are operating from a standpoint of hindsight. Because we know that the Civil War eventually took place, we look for what historians call "causation." Yet we must also be careful not to ask leading historical questions. To wit, we must ask if such historical trends add up to being the cause of the war, or whether or not they might have portended alternative outcomes.

This first lecture will spend most of its time looking at factors other than slavery, racial attitudes, and politics, which we will examine in greater detail in our next lecture.

Growth and a divergent North and South

All of America grew at a rapid rate during the last decade of the antebellum era, but the nation did not grow everywhere at the same pace. A commonly held perception about the Civil War's causation is that the slaveholding South was a backward place that had drifted politically, culturally, socially, and economically away from the American mainstream as represented by the North. Yet if we look at indices of economic and demographic growth, we must acknowledge that it was actually the North that had become radically different from the South in the first half of the nineteenth century. For sure, slavery had always been a point of division between the two regions, but the economic explosion that occurred in the North between 1840 and 1860 set it apart not only from the South, but the rest of the world. With the exception of England, in many ways the South was actually much more like Europe, both in economic growth and social structure.

Immigration and natural increase made antebellum America grow. It was more telling, however, in the North:

Urbanization and Antebellum America: Some Statistics

City 1850 Rank 1860 Rank

New Orleans 116,375 5 168,675 6

Charleston 42,985 15 40,522 22

Richmond 27,570 26 37,910 25

Wilmington, NC 7,264 99 9,552 100

St. Louis 77,860 8 160,773 8

Chicago 29,963 24 112,172 9

Cleveland 17,034 41 43,417 21

Indianapolis 8,091 87 18,611 48

States: 1850 (slave) 1860 (slave) RG=Rate of Growth

Illinois 851,470 1,711,951 RG = 101%

Ohio 1,980,329 2,339,511 RG = 18%

Minnesota 6,077 172,023 RG= 2730%

Tennessee 763,258 (239,459) 834,082 (275,719) RG = 9% (15%)

Georgia 524,503 (381,682) 505,088 (462,198) RG = - 3.7% (21%)

Louisiana 272,953 (244,869) 376,276 (331,726) RG = 37.8% (35%)

While immigrants, overwhelmingly from Germany and Ireland, flooded into the North in great numbers, native-born Americans of all regions were also on the move within the borders of the United States and its territories, often seeking out new opportunities further west. This resulted in Americans of differing regions and values coming into direct contact with one another, especially in places like Kansas, Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, Nebraska, Arkansas, Texas, and California.

Technology:

Yet America's great antebellum migrations were not simply driven by immigration and the need for land. Emerging technologies of the antebellum era also lent shape to the directions in which young America traveled. Steam, both on rivers and rails, played an important role in America's economic expansion in the antebellum era. If you could imagine riding on this contraption! In time rail became more significant because it integrated the economies of the North on an east-west basis, and led to greater economic isolation between North and South. Consider the following maps and the impact of transportation networks on the fate of the nation.

Map: Potential routes of the transcontinental railroad in 1850 (Library of Congress)

Map: The growth in rail lines between 1850 and 1860 (Allyn Bacon Longman)

Technology also went hand-in-hand with urbanization. Technology also worked to transform the societies that produced new things particularly when viewed on a human-scale basis. Small scale innovation relied upon countless "mechanics" who labored in their workshops. Remember, that the 1850s were a time generally before engineering became a profession. Many developments came about in an unscientific trial-and-error method. Such developments favored the culture of the shopkeeper in the North. Indeed, the fact that the North developed an urban culture of mechanics reveals a great deal about its divergence from the South in terms of social and economic development. Let's consider the differences in the way antebellum men viewed themselves based on these daguerreotypes from the Library of Congress of shopkeepers at their professions:

In these pictures we see the development of a growing class outside of the agrarian tradition.

The rapid economic and technological transformation that took place in the North also transformed its culture in a way that made it diametrically opposed to prevailing institutions in the South. What it meant to be a free white man differed considerably in the two regions.

The culture of the Antebellum South: Patrons and Clients and Paternalism

Although it isn't necessarily a fair comparison to make between the work of Mayer and the daguerreotype of the northern blacksmith, there is something to it.

Deconstructing what it meant to be a southern man.

Social inequality was arguably a more prominent feature in the South than in the North. Elites of both regions might blanche at the "creeping democratization" that they had seen in America in the last thirty years, but with the free labor culture in the North, such democratization was able to more fully manifest itself in political ways. Much of this had to do with urban centers and the growing impersonality of financial institutions in the North. In the far more rural South, personal connections were essential to one's economic health - particularly with regard to that mother's milk of agriculture and commerce - credit.

To use a term associated with Ancient Rome, the social relationships between men operated in the South operated on a patron-client basis. This system of mutual obligations tied southern elites to the middling classes and was particularly useful in a rural social and economic milieu. I will spend a fair amount of time in class discussing the many manifestations of this system.

Paternalism and patriarchy, while hardly unknown in the North, were also essential to the societal, familial, and gendered relationships in the South.

Modernizing and the South

The South was also interested in modernizing, but had to approach technology and innovation in a way that was compatible with southern cultural values. Perceptions of the South as a strictly agricultural economy, while generally true, are misleading. Younger southerners in particular saw modernization as a way to allow the South to regain its leadership role. Yet others feared what technological innovation and the growth of manufacturing might mean to southern social structure - that it might force the South to become more like the North in ways that southern elites feared. The challenge, then, was to both modernize the South while preserving its cultural fabric.

Beyond "North" and "South" : A Lesson for the Times

We can overstate the differences between the antebellum North and South. While I can certainly point to many examples like the ones in the images above that depict stark contrasts in the livelihoods and worldviews of the two regions' men, it was hardly so clear cut. As historian Peter Carmichael has shown, young Virginians were looking as much toward modernization and the growth of industry as many of their northern counterparts. Along the border states of Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Tennessee, southern parts of Illinois, Missouri, farmers of all kinds faced the same basic problems and held similar values. Many elite southern men attended college in the North and individuals engaged in all manner of industry conducted business that brought them into economic interdependence across regions. Perhaps the most sobering reality in acknowledging this is that Americans had much more in common with one another than they had real differences. As we will see in the next lecture, however, political rhetoric, a crisis in leadership, and the random nature of historical contingency would plunge the nation into its bloodiest war.

Between 1840 and 1860, the United States underwent many transformations. The following are a few of the important ones:

- Westward expansion and internal migration

- Rapid technological advances

- Immigration and population growth

- Political change

Students of the Civil War rightly focus a great deal of attention on the antebellum period in order to ascertain the moment when "it all went wrong." Historians, of course, are operating from a standpoint of hindsight. Because we know that the Civil War eventually took place, we look for what historians call "causation." Yet we must also be careful not to ask leading historical questions. To wit, we must ask if such historical trends add up to being the cause of the war, or whether or not they might have portended alternative outcomes.

This first lecture will spend most of its time looking at factors other than slavery, racial attitudes, and politics, which we will examine in greater detail in our next lecture.

Growth and a divergent North and South

All of America grew at a rapid rate during the last decade of the antebellum era, but the nation did not grow everywhere at the same pace. A commonly held perception about the Civil War's causation is that the slaveholding South was a backward place that had drifted politically, culturally, socially, and economically away from the American mainstream as represented by the North. Yet if we look at indices of economic and demographic growth, we must acknowledge that it was actually the North that had become radically different from the South in the first half of the nineteenth century. For sure, slavery had always been a point of division between the two regions, but the economic explosion that occurred in the North between 1840 and 1860 set it apart not only from the South, but the rest of the world. With the exception of England, in many ways the South was actually much more like Europe, both in economic growth and social structure.

Immigration and natural increase made antebellum America grow. It was more telling, however, in the North:

Urbanization and Antebellum America: Some Statistics

City 1850 Rank 1860 Rank

New Orleans 116,375 5 168,675 6

Charleston 42,985 15 40,522 22

Richmond 27,570 26 37,910 25

Wilmington, NC 7,264 99 9,552 100

St. Louis 77,860 8 160,773 8

Chicago 29,963 24 112,172 9

Cleveland 17,034 41 43,417 21

Indianapolis 8,091 87 18,611 48

States: 1850 (slave) 1860 (slave) RG=Rate of Growth

Illinois 851,470 1,711,951 RG = 101%

Ohio 1,980,329 2,339,511 RG = 18%

Minnesota 6,077 172,023 RG= 2730%

Tennessee 763,258 (239,459) 834,082 (275,719) RG = 9% (15%)

Georgia 524,503 (381,682) 505,088 (462,198) RG = - 3.7% (21%)

Louisiana 272,953 (244,869) 376,276 (331,726) RG = 37.8% (35%)

While immigrants, overwhelmingly from Germany and Ireland, flooded into the North in great numbers, native-born Americans of all regions were also on the move within the borders of the United States and its territories, often seeking out new opportunities further west. This resulted in Americans of differing regions and values coming into direct contact with one another, especially in places like Kansas, Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, Nebraska, Arkansas, Texas, and California.

Technology:

Yet America's great antebellum migrations were not simply driven by immigration and the need for land. Emerging technologies of the antebellum era also lent shape to the directions in which young America traveled. Steam, both on rivers and rails, played an important role in America's economic expansion in the antebellum era. If you could imagine riding on this contraption! In time rail became more significant because it integrated the economies of the North on an east-west basis, and led to greater economic isolation between North and South. Consider the following maps and the impact of transportation networks on the fate of the nation.

Map: Potential routes of the transcontinental railroad in 1850 (Library of Congress)

Map: The growth in rail lines between 1850 and 1860 (Allyn Bacon Longman)

|

| The Illinois Central in 1850 |

|

| Confluence of the Ohio, Cumberland, Tennessee, and Mississippi River Valleys |

A watchmaker at his bench.

A blacksmith in his shop. Note that he's more than a farrier, he has the tools of the practical engineer nearby. The photo, like the one of the watchmaker, is an expression of masculine pride.

Here merchants in antebellum Philadelphia pose in front of their shops.

In these pictures we see the development of a growing class outside of the agrarian tradition.

The rapid economic and technological transformation that took place in the North also transformed its culture in a way that made it diametrically opposed to prevailing institutions in the South. What it meant to be a free white man differed considerably in the two regions.

The culture of the Antebellum South: Patrons and Clients and Paternalism

"Leisure and Labor" by Francis Blackwell Mayer

Although it isn't necessarily a fair comparison to make between the work of Mayer and the daguerreotype of the northern blacksmith, there is something to it.

Deconstructing what it meant to be a southern man.

Social inequality was arguably a more prominent feature in the South than in the North. Elites of both regions might blanche at the "creeping democratization" that they had seen in America in the last thirty years, but with the free labor culture in the North, such democratization was able to more fully manifest itself in political ways. Much of this had to do with urban centers and the growing impersonality of financial institutions in the North. In the far more rural South, personal connections were essential to one's economic health - particularly with regard to that mother's milk of agriculture and commerce - credit.

To use a term associated with Ancient Rome, the social relationships between men operated in the South operated on a patron-client basis. This system of mutual obligations tied southern elites to the middling classes and was particularly useful in a rural social and economic milieu. I will spend a fair amount of time in class discussing the many manifestations of this system.

Paternalism and patriarchy, while hardly unknown in the North, were also essential to the societal, familial, and gendered relationships in the South.

Modernizing and the South

The South was also interested in modernizing, but had to approach technology and innovation in a way that was compatible with southern cultural values. Perceptions of the South as a strictly agricultural economy, while generally true, are misleading. Younger southerners in particular saw modernization as a way to allow the South to regain its leadership role. Yet others feared what technological innovation and the growth of manufacturing might mean to southern social structure - that it might force the South to become more like the North in ways that southern elites feared. The challenge, then, was to both modernize the South while preserving its cultural fabric.

Beyond "North" and "South" : A Lesson for the Times

We can overstate the differences between the antebellum North and South. While I can certainly point to many examples like the ones in the images above that depict stark contrasts in the livelihoods and worldviews of the two regions' men, it was hardly so clear cut. As historian Peter Carmichael has shown, young Virginians were looking as much toward modernization and the growth of industry as many of their northern counterparts. Along the border states of Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Tennessee, southern parts of Illinois, Missouri, farmers of all kinds faced the same basic problems and held similar values. Many elite southern men attended college in the North and individuals engaged in all manner of industry conducted business that brought them into economic interdependence across regions. Perhaps the most sobering reality in acknowledging this is that Americans had much more in common with one another than they had real differences. As we will see in the next lecture, however, political rhetoric, a crisis in leadership, and the random nature of historical contingency would plunge the nation into its bloodiest war.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)